The beginning of our exploration

The tale of Emperor Yao inventing Go to educate his son Danzhu may be unverifiable, yet the profound history of Go remains indisputable. Across East Asia, Go is a beloved pastime, and professional Go players are held in high regard. Despite its straightforward rules, Go harbors boundless complexity in its gameplay, earning it the reputation of an eternal game within the cosmos. Attempts to popularize this ancient board game in alternative formats have seldom met with success.

The tale of Emperor Yao inventing Go to educate his son Danzhu may be unverifiable, yet the profound history of Go remains indisputable. Across East Asia, Go is a beloved pastime, and professional Go players are held in high regard. Despite its straightforward rules, Go harbors boundless complexity in its gameplay, earning it the reputation of an eternal game within the cosmos. Attempts to popularize this ancient board game in alternative formats have seldom met with success.

Playing Go on a spherical surface is a problem that many have already considered. However, the adaptation of a quadrilateral grid to a sphere, although there are schemes like Cube Sphere, which introduces 8 special points, presents challenges. People have realized that another possibility is to introduce other possible topological structures for the board. Our attempt is to take a step in this direction.

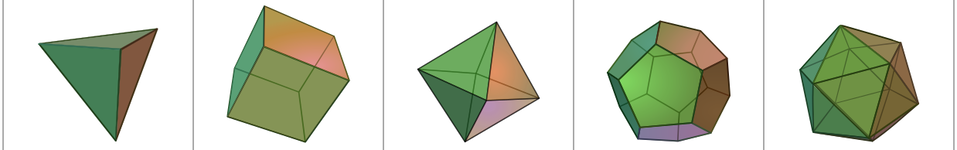

Back in the era of Plato in ancient Greece, people already knew that there are only 5 types of convex regular polyhedra in the world, known as the Platonic solids. These polyhedra have faces that are all identical regular polygons. They include the tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedron.

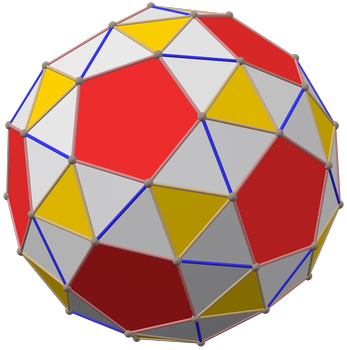

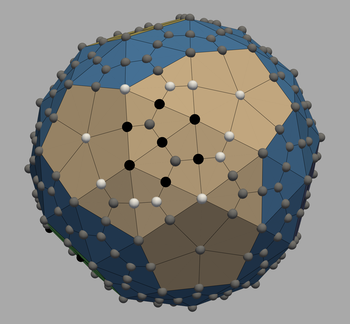

With just a simple glance, it's evident that using them as game boards offers very high symmetry. However, the vertices for placing pieces are too few, making them unsuitable for complex games. Further contemplation led us to the Archimedean solids. Archimedean solids are convex polyhedra constructed using two or more types of regular polygons as faces. They were first discovered by the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes in the 3rd century BC. There are a total of 13 Archimedean solids. Among them, the most interesting is the snub dodecahedron, which boasts 80 equilateral triangular faces, 12 pentagonal faces, 60 vertices, and 150 edges. This polyhedron exhibits very high symmetry and is the closest to a spherical shape among all Archimedean solids. It's this near-spherical property that makes it our choice. Only such mathematical perfection can inspire us to explore a new game that is eternal.

So, can this choice offer enough complexity? A quick calculation yields 80 + 12 + 60 + 150 = 302, which, although fewer than the 361 grid points in Go, is still a substantial number and can provide the foundation for a challenging game. Additionally, this implies that in this new game, we must consider vertices, edges, and faces simultaneously, posing a fascinating design challenge as we aim to preserve the original rules of Go. After careful consideration, we have devised the following game board.

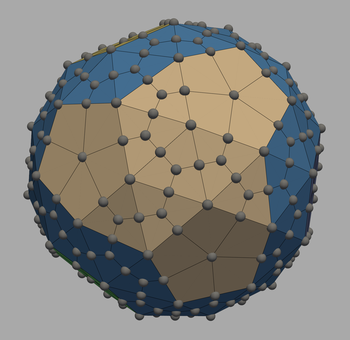

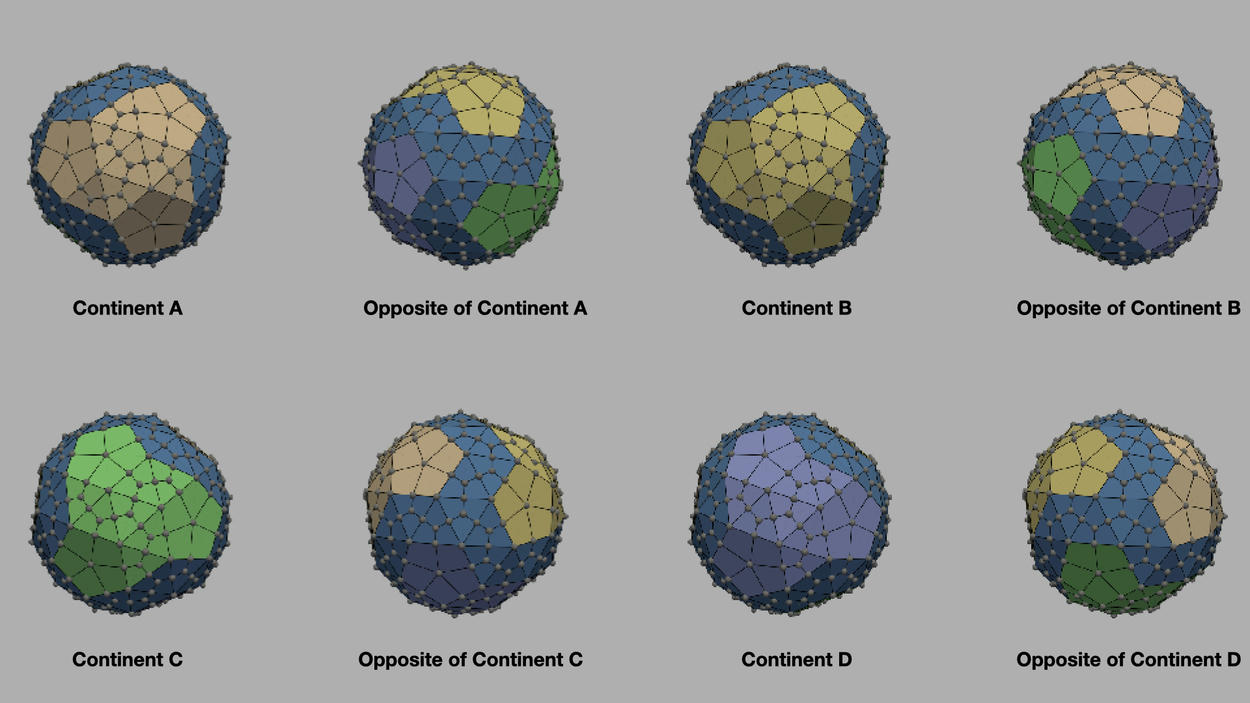

Attentive readers may have already observed that the game board background features different colors, indicating "continent" and "ocean." This is necessary due to the highly symmetrical nature of the game board, where additional information is required to provide absolute positioning. The absolute positioning system has been meticulously considered and calculated. It must align with human cognitive patterns, avoid excessive complexity, and still offer absolute positions for placing pieces.

Simply put, three neighboring pentagons constitute a "continent," resulting in a total of four "continent" on the game board. These four continent correspond to four axes of symmetry, with the ocean opposite each continent. This design enhances the visual intuitiveness and enjoyment of our game. Naming the four continent could be considered, echoing certain legends in human cultural history, such as the Four Great Continents in Buddhism: East Purvavideha, South Jambudvipa, West Aparagodaniya, and North Uttarakuru. However, we prefer not to finalize these elements immediately but rather seek to refine the spatial aspects of the game through a process of consensus.

In introductory Go classes, we're all familiar with the saying "金角银边草肚皮" (gold in the corners, silver on the sides, grass in the center). So, what rules will govern this new game? This is a question we'll delve into below. It's easy to observe that the game board features points of degrees three, four, and five. The original vertices of the snub dodecahedron are all points of degree five on the game board, the centers of equilateral triangle faces are points of degree three, the centers of pentagon faces are points of degree five, and the points of degree four are all midpoints of edges. On average, what's the degree of the grid points on the game board? We can easily calculate this: there are 80 points of degree three, 12 + 60 points of degree five, and 150 points of degree four, totaling 302 points. The average degree is 3.97, which is very close to 4. This suggests that, on average, our game board closely resembles a four-degree board. It's also easy to understand that points of degree three are more prone to becoming empty than points of degree five. Given that pentagons have larger areas than triangles, we're considering adopting an area-based scoring rule rather than a point-based one. Such a rule will make the game more intriguing, as areas that are easy to empty will be smaller, while those that are not will be larger.

Lastly, let's showcase a live shape example. In the illustration above, the black stones represent the smallest live shape in this game, requiring only 7 stones. This is remarkably close to Go, where 6 stones are needed for a live shape. This example highlights the intrigue and challenges of our game.